Just seventeen. Just passed the driving test. The world at my feet.

Any risk of Montegos, Maestros and Metros disappearing from our roads is scarcely surprising. They have been rusting away for years. Only well-looked-after or museum pieces survive to be judged in Dove Publishing’s classic books. There was always a case for preserving a few just to remind us how bad they were. I road tested Austins in the 1960s that demanded a grease gun applied to 13 points every 1,000 miles. It’s astonishing they have lasted long enough for John Mayhead, UK editor of the Hagerty Price Guide to claim: “There is a sense of nostalgia for these cars. People have a strong emotional connection to them.”

Maybe. I would love to drive an Austin Sixteen, like the one in which I passed my driving test, for Auld Lang Syne. Father was in steel and, impressed by a metallurgist who told him Austin was fussy over material for gears, bought one. Dependable Austin, it had Longbridge’s first overhead valve 2199cc 4-cylinder, cart springs, yet a decent turn of speed (75-80mph).

Leather-upholstered with neat little armrests, an Austin Sixteen was strongly made with a cross-braced chassis and the family grew to like it, despite being slightly declassé compared with previous wood and walnut Wolseleys. Former 1920s Lancia designer Dick Burzi brought in the rounded, slightly transatlantic grille for 1939, and applied it later to his Austin A40 and A70.

“Classic” Austins, it seems according to Hagerty an enthusiast vehicles insurer, have gone up by 14 per cent. Last year Allegros (remember the “quartic” steering wheel) made between 1973 and 1983, averaged £2,425 and now cost £2,755. Not perhaps investment class but encouraging enough for Mayhead to claim: “Since the end of the first Covid lockdown last year, there has been a surge in demand for all types of classic cars. Dealers believe it’s a result of people being aware of what's important in life.”

Hagerty’s thinks isolation and limited social interaction have led to car lovers reflecting on vehicles from their childhood. Savings accrued through working from home has led to demand for cars not hitherto regarded as classics but with sentimental significance.

We were a Wolseley family really. This 6/80 replaed the Austin.

I’m not convinced. Father went back to Wolseleys, an Armstrong Siddeley I talked him into, and a big Vanden Plas Princess I inherited to tide me over a lean time. But when he retired and downsized to an automatic Vanden Plas 1300, really an ADO16 with fancy trim, it was a disaster. I had to pull motoring correspondent rank and complain, driving it to Longbridge once to get it fixed. It never was. There is a limit to nostalgia.

Back to posh. The Armstring Siddeley 236 was not quick like the 234 but it was smooth.

But then, what about my MGA, Austin-Healey Sprites, dear long-stroke Wolseley 4/44, rallying my Mini, success in a Sunbeam Rapier? Nostalgia? Teen trysts in a Triumph? Some cars were more memorable than others. Some should have become family heirlooms, like my MGB with Twin-Cam conversion eventually sold by Brooks at Goodwood. One that does survive was my BMW Z3 still cherished by Craig. But it’s not just cars you owned that pull heartstrings. My Sunday Times long-term Vauxhall Senator, a relaxing sofa of a car, is fondly recalled over family holidays in Devon, as well as the Ford Maverick with roof-box and trailer that went to the Hebrides with daughters, step-daughters, dogs and pretty well everything piled inside.

Second Sprite, Turnberry Ayrshire, 1962.

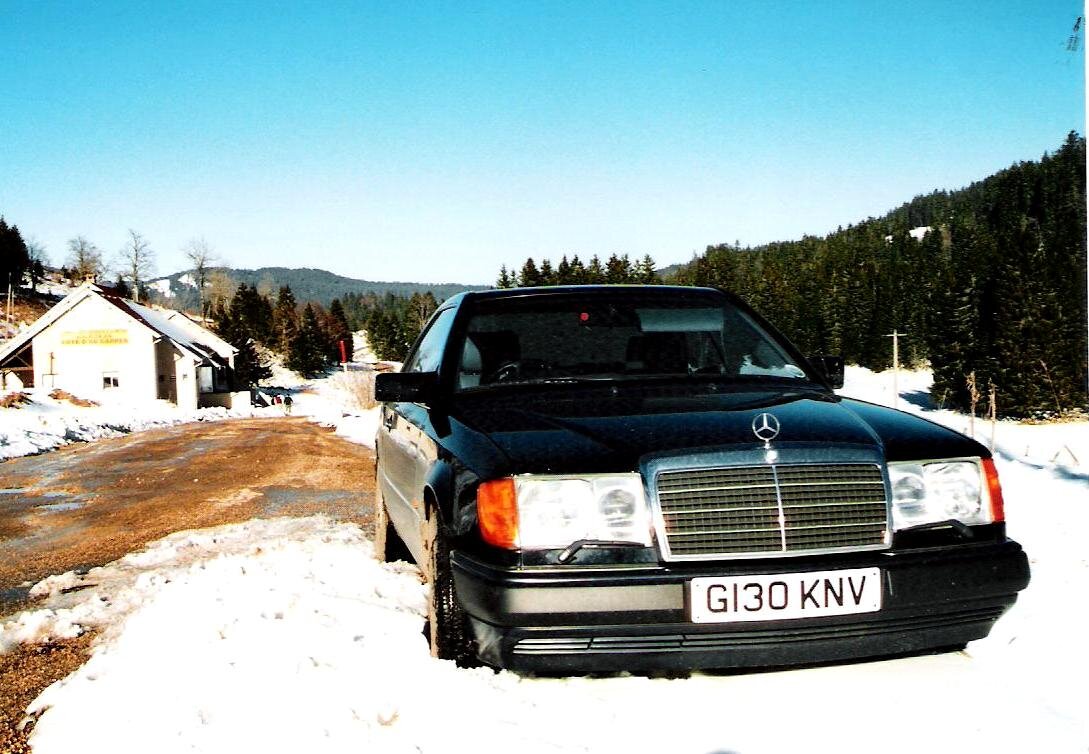

Ten-thousand-mile test cars became part of the family, like the Mercedes-Benz 300CE-24 we used to cover the Pirelli Alpine Marathon. Pressed to reach a ferry with no time to change drivers, the crew kept Ruth to a steady 130mph for much of the A10 Autoroute to Ostend. I don’t think she ever did it again, but it was good to know that, when encouraged, she could.

Mercedes-Benz 300CE-24 Twelbve-month 10,000-mile Sunday Times test car.

Maybe Hagerty was right that everyday cars were the backbone of Britain in the 1980s and 1990s. What it calls "unloved workhorses" that would eventually be scrapped, their symbolism lasted rather better than their flimsy build. “Enthusiasts are snapping up survivors because of an emotional connection or sometimes perhaps because they feel a duty to preserve them for the enjoyment of future generations.”

My first MG. 1950s, open rain, hail, or shine was “macho”. We thought.

Sunbeam Rapier, favourite rally car, prepared by the works for a cancelled Alpine rally, it had chassis bracing that improved the handling.

16-valve converted MGB, fresh bodyshell, 5-speed garbox, with nostalgic restored Austin A30.